Read the previous entry in the series here.

Read the next entry in the series here.

Following an in-milieu commentary about the Catalyst Wildeye, “A Full House” begins with the arrival of Shun at Withywoods; her reception is detailed, along with Fitz’s wonderings about her situation and circumstances. Fitz also ruminates on the shifts in his relationship with Bee, as well as on the work that has been done on the estate to bring it back into full operation. Shun is visibly displeased with the setting; Riddle, who accompanies her, is somewhat amused. Bee, in the thrall of one of her visions, enters and draws Fitz away, where he finds the Fool in dire straits.

Photo by Suzy Hazelwood on Pexels.com

Fitz takes up the Fool and begins to attend to him–finding him a her, and not the Fool, though much like him. She rouses under his ministrations and reports being sent as a messenger to him. Amid the report, Riddle intrudes, and Fitz tasks him with finding assistance. As Riddle departs on the errand, Fitz assigns tasks to Bee, as well, though she remains to confer briefly with him. The messenger delivers what of the message she can, although she notes that she has likely preceded danger.

Fitz leaves off the messenger to attend to Shun, who is verbally displeased at her situation and lays out her objections at length. Fitz realizes the depths of Shun’s despair, and he reaches out to her–only to be interrupted by Bee, who reports that the messenger has departed in haste. Fitz begins to puzzle out the issue as Riddle returns, and he and Bee move to investigate. Wariness begins to settle onto Fitz once again, and Bee begins to take it up, as well.

The present chapter does a fair amount of foreshadowing–it can hardly not, what with prophetic figures at play and the overt discussion of coming dangers from multiple sources, as well as Fitz’s admission of his lapsing wariness and assassin-appropriate paranoia (although it’s not paranoia if there are people out to get you). Too, it is the second appearance of a strange, pursued messenger in the narrative, and simple narrative structure suggests that a third will arrive. (Interestingly, the first messenger was almost completely missed, while the second was received but not fully. Narrative tropes suggest that the third messenger will deliver the message in full, but some other break will occur; typically, the first two set a pattern that the third violates. Admittedly, however, there is precedent for a decline in threes; the example of Lancelot’s judicial combat defenses of Guinevere comes to mind as an example for me for what may be an obvious reason.) Consequently, there’s some forward-looking at work, and at both narrative and structural levels, something I appreciate seeing.

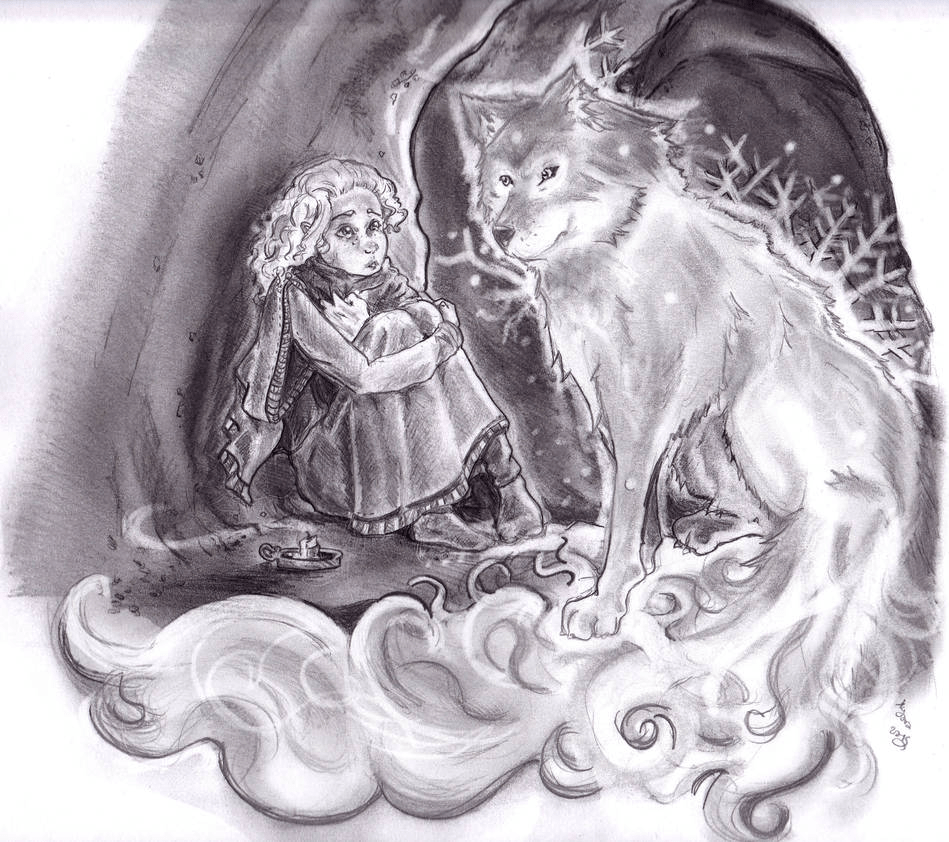

I note, too, that the present chapter returns to something identified by several sources (as attested here) as something of a motif in the treatment of the Fool and his people: gender fluidity. While the term is not used within Hobb’s work (so far as I recall), the concept it describes very much is, and it surfaces in the present chapter in confusion about the messenger. Bee predicts that a man has arrived, and Fitz accepts the prediction as stated until presented with physicality that belies it–although the Fool had noted (and had been depicted as) being flexible in the expression and presentation of gender, something about which Fitz knows (and should know better than to assume). The notion of physicality determining gender, then, is not a stable one among the Fool’s people (nor necessarily among Fitz’s), and, given the foreshadowing at work already, it has to be thought that that flux will be of some moment, moving forward.

If you’d like me to write to order for you, I’m available!