Read the previous entry in the series here.

Read the next entry in the series here.

The following chapter, “Challenges,” opens with translated in-milieu commentary about mapmaking in the Outislands. It moves to Fitz’s departure from Jinna on amicable but tentative terms with her. He glosses the passage of several days and the events, noting the continued avoidance of the Bingtown delegation by the Narcheska and her uncle. Fitz and Chade confer about the implications of the strained relations among the three parties, as well as about Fitz’s tense relationship with Starling. They also talk of Dutiful’s suspended Skill lessons–Selden’s presence makes them perilous–and the Narcheska’s afflictions by tattoo and Henja.

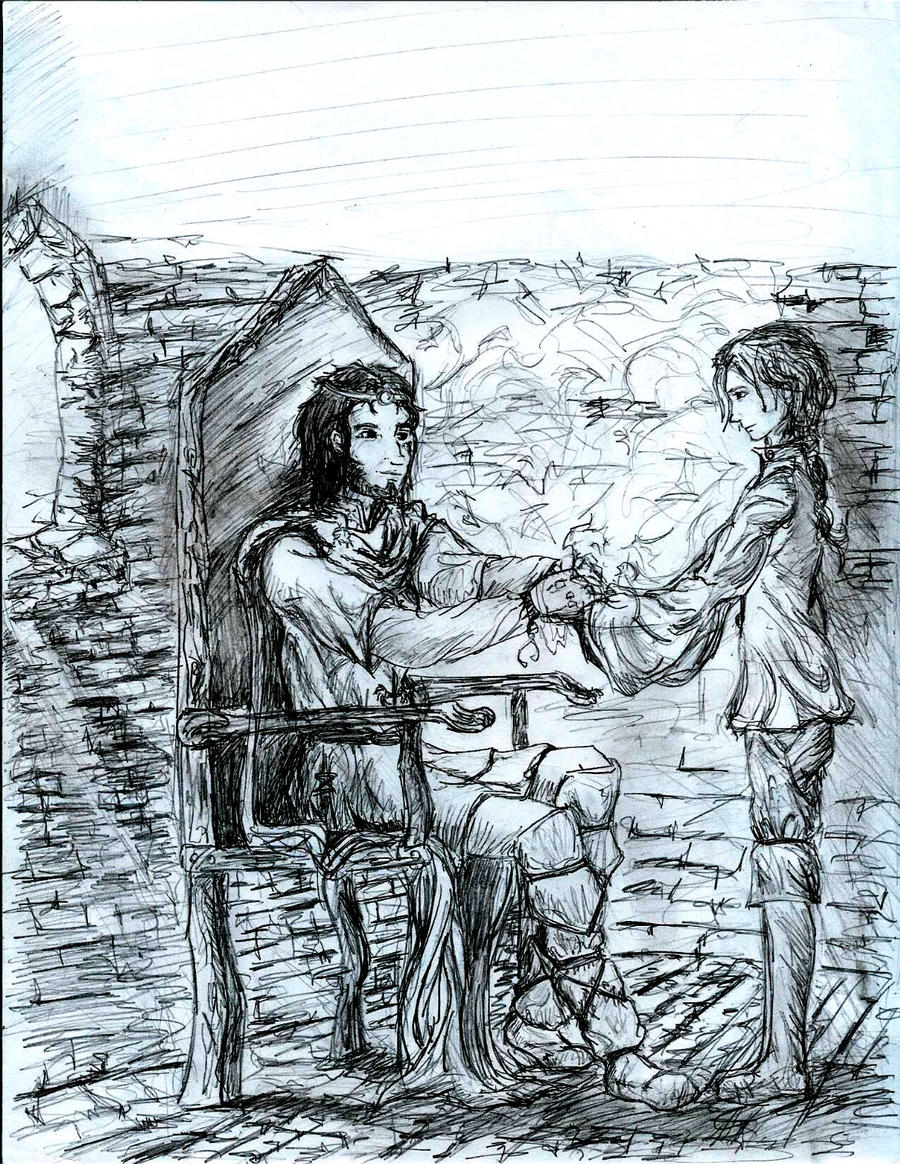

Image is from Faceless Trey’s Tumblr, here, used for commentary.

Fitz additionally chews over the strain in his feelings towards the Fool, Chade commenting aspersively on them; they also talk briefly of Hap, Fitz recalling Hap coming to him. They part to prepare for their evening’s work, Chade acting as councilor and Fitz as spy in the tunnels. He observes as Elliania and Peottre make a delayed entrance and the Narcheska voices doubts about the betrothal. She issues a challenge, and Dutiful erupts into acceptance of it before he can be halted, whether by Kettricken’s words or Fitz’s Skill-command–the latter of which he sets aside. Dutiful issues one, in turn, which Elliania accepts; if he is to slay the dragon Icefyre, she must accompany him to see it done–or to affirm there is no dragon to slay. In a generally approving tumult, the betrothal is formalized, and a toast is drunk to the intended couple.

The present chapter is near to the middle of the book, and the present novel is the second in the trilogy; it’s as near to the center of the series as could be desired. For those taught with Freytag’s pyramid in mind, it is a “natural” place for the climactic action to occur–and the mutual challenges and acceptances would seem to fit that rubric. While this is not the inciting incident of the plot–not even as presented in the novels, let alone within the broader context in which the events depicted exist–it is a cause of much of the action to come, as well as marking off the end of what is primarily explication (in the “main” plot, at least, or the one concerned with the fates of peoples and nations). Hobb does demonstrate a tendency to make such moves in her work; I’ve noted it before, here, here, here, and here, if not elsewhere. It’s not to be wondered at, then, that she does it again.

And as far as ways to make that climax happen go, teenagers are great. Ill-considered emotional outbursts come off as authentic, verisimilitudinous, from hormone-riddled people whose brains remain in development, after all…

![r/DnD - [OC] Schools of Magic Periodic Circle](https://preview.redd.it/gd87qcqb3sw11.png?width=960&crop=smart&auto=webp&s=e47fdab4ded5065b7f96eeb4903f280643b9db1a)