Read the previous entry in the series here.

Read the next entry in the series here.

A chapter titled “Revelations” comes next, opening with Fitz’s reflective musings on fate before moving into the resumed journey towards Forge. Fitz wakes and eats as the ship he and Chade had boarded continues towards the village, and he notes the effects of a powerful stimulant–carris seed–on Chade, rebuking him amid an explanation of its effects. Chade sets Fitz’s concerns aside and briefs him on the upcoming mission.

Fitz and Chade proceed in haste towards Forge, Fitz musing on the comfort of being able to place trust in another, Chade reminiscing about his youth. They arrive at Forge too late to save it–or its inhabitants, who act erratically and who are opaque to Fitz’s Wit. He reflects on the sense and its absence in others and narrates his sudden panic at the revelation, panic that pushes him to drag Chade away. In explaining his actions to his mentor, he intimates his abilities to him, though Chade appears not to understand.

As they make to return to Forge, they are seen by people from a neighboring village who have come to check on their attacked neighbors. Chade is seen, an his likeness to a harbinger of plague is noted, worsening the situation and prompting him and Fitz to flee. After they are safe, Chade expounds on the problem of his having been seen as such and of the threat raised by the new Red-Ship raids that leave their victims disconnected from one another.

The effects of the carris seed leave Chade suddenly, and Fitz has to get the two of them and their horses back to the ship that had borne them. They return to where Verity is concluding his visit with Kevlar, and Fitz learns that, while his own mission has been a success, rumors of what happened at Forge are spreading already, bringing fear and the start of despair to the Six Duchies.

The chapter introduces the Forged, those afflicted by means later books make clearer and stripped of the ability to connect emotionally to themselves or to others. The parallels between the Forged and zombies have been noted by others (here and here among a great many), so I do not need to belabor the point, but it is notable that the Forged Ones, even in their first appearances, evoke the panicky terror of the uncanny valley. They are too much like Fitz–and the reader–to be truly Other, and they are afflicted rather than choosing, so that they should be recipients of sympathy. But they are already horrible, terrible things that provoke revulsion, precisely because they are like those with whom readers already sympathize; they may not be evil, as such, but they cannot be abided, even so.

(When I first read the novel, many years ago, I was not the kind of person who attended to political parallels. Nor am I up enough on what was going on in the world when the book was released [and, presumably, written] to be able to comment on that parallel with any accuracy. But as I read now, I wonder if the Forged Ones do not read as a backhanded comment on the fears too many have about immigrants and terrorists, that their machinations will somehow corrupt the hardworking, virtuous folks with whom they come into violent contact. Given their ultimate source…the comment becomes an interesting one. I might return to the idea in later posts in the series. It might bear some explication.)

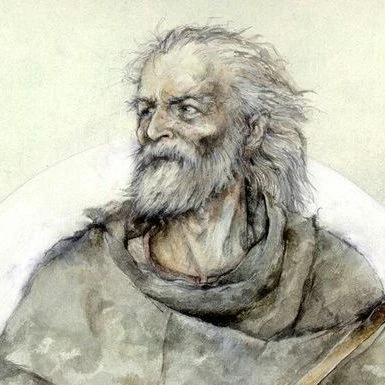

Something I’ve noted as I’ve looked for art for these pieces is that there seems a fairly sharp divide among portrayals of the Farseers. Most of the works I’ve seen depict them as white, following Tolkienian conventions. A few, though, and many of the better ones, depict them as persons of color, whether as Black folks or as more closely akin to Native American and First Nations peoples. (For the record, I think the latter more accurate, given my earlier arguments about the milieu being more of the Pacific Northwest than the medieval European northwest and the oft-noted geographical similarities between the Six Duchies and Alaska.) I tend to think the persons-of-color depictions better in line with the text, else there’d not be quite so much made of–well, that will come later in the text. I also tend to think it a good thing, reminding readers that the medieval of which Hobb’s work partakes is not quite the monochromatic thing it is too often, and all too unhelpfully, assumed to be. (Helen Young has more to say on the matter.) It’s a bit of an aside, I know, but still a useful one.