Read the previous entry in the series here.

Read the next entry in the series here.

The next chapter, “Strategy,” begins with what seems a nursery rhyme before turning to continued efforts to keep Fitz centered and attentive. The efforts are not entirely successful, and they seem less so because Fitz uses the Wit. That the road they travel is to blame is clear, and that it is a strange and powerful road is also clear. Strangely, amid the discussion of Fitz’s situation, the Fool and Starling arrive at some rapproachement. Nighteyes brings meat with him when he returns, which also helps.

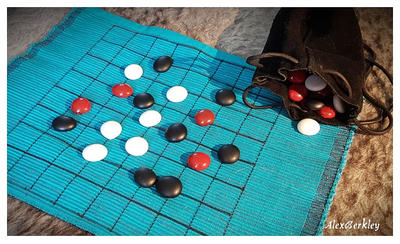

kettles stone game by AlexBerkley on DeviantArt, here, used for commentary

With bellies full and needing to keep Fitz focused, the party takes turns singing and reciting through the evening. Kettle dislikes Fitz’s selection and seems to aim hers at him, though he does not understand why. Kettricken confesses her feelings of failure, and Fitz begins to learn a strange game under Kettle’s tutelage. Kettle avers that it is a game from Buck, though Fitz does not know it. She sets a puzzle in it for Fitz that he takes to sleep with him; Nighteyes gives him the answer to the puzzle, equating the puzzle to a hunting pack.

When Fitz presents the solution, Kettle is surprised at it. She asks him after his Wit-bond with Nighteyes. Starling and the Fool comment after Fitz answers, and the party slowly breaks camp. Fitz is bidden walk, accompanied, beside the road rather than upon it; the Fool goes with him, taking the opportunity to confer about Kettle and try to puzzle her out. That afternoon, Starling succeeds the Fool and inquires about the Fool’s history–particularly the romantic history. That evening, Kettle puts Fitz to another puzzle; he does not come to an answer before joining Nighteyes in a nighttime romp and sleeping deeply until morning.

The stone game Kettle presents to Fitz is a point of particular interest, not only in the chapter (where it occupies a fair bit of the text, as well as of the narrating protagonist’s attention), but also in terms of worldbuilding. All fiction depends for its effectiveness on what Coleridge calls the “willing suspension of disbelief,” the audience’s gracious acceptance that, within the fictional milieu presented, the actions presented can happen as they are shown and should happen as they are shown. In “On Fairy-stories,” Tolkien can be paraphrased as asserting that the willingness to suspend disbelief is aided by the closer correspondence of the fictional world to that of the audience; Hobb herself reaffirms such an opinion, noting in “5000 Words about Myself” that “I think the best way to convince a reader that I know what I’m talking about when I recount the habits of dragons is to know what I’m talking about when I recount the details of raising chickens or putting a roof on a house.” And while it is the case that the rules of the stone-game are glossed over in the text, the mere presence of that game is itself a detail enhancing the text’s verisimilitude.

It does so in that it points out the presence of recreational activities among the people of the Six Duchies. Admittedly, Hobb motions to such things earlier in the series; there are scenes of drinking and various kinds of gambling, as well as the depravities of Regal’s gladiatorial contests. But having someone take a table game along on an expedition into mountains bespeaks an attachment to such things that does not often feature in Tolkienian-tradition fantasy literature; it is difficult to imagine hobbits carrying dice or cards with them as they traipse about Endor, for example. But people in the real world often do so, perhaps more easily in the era of smartphones than previously, but not without earlier parallels.

Too, the stone-game is a valorization of play, more generally. More than anything else the traveling party has available to it, the game serves to keep Fitz grounded in the real and present, rather than being swept away by the magic that surrounds them. It may seem somewhat paradoxical to have a game–inherently a distraction from immediate concerns–serve as an anchor in the real, but there are no few who note the utility of play to daily life and work. (This bit comes to mind. There are others.) And maybe more folks could stand to have a little more enjoyment of such things.

[…] Read the previous entry in the series here. Read the next entry in the series here. […]

LikeLike

[…] the previous entry in the series here. Read the next entry in the series […]

LikeLike

[…] on the present passage, though: I note with some interest the reported development of the Stones game Fitz had learned from Kettle and passed on to Dutiful as part of his Skill training. Having become […]

LikeLike