The paper below was the first one I had published (in the now-defunct Studies in Fantasy Literature); it was written early on in my graduate schooling. Since it’s out of print–and has been for a while–and I was looking back over old work, I figured, eh, what the hell.

Mind the changes, which include use of a now-outdated citation style. And please let me know in comments what all you think of them (though note that comments are moderated in this webspace).

I do not remember a time in my life when I have not been reading fantasy literature. Over my years of readings I have encountered fantasies well- and poorly-written, those that make sense and those that do not, those that try to cloak their otherworldliness and those that flaunt it. Not until I reached the end of my undergraduate work in college, however, did I begin to look at the scholarly criticism of that genre in which I had and have so long delighted; when I looked, I was surprised to learn that aside from the works of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, and, more recently, J.K. Rowling (and I do not mean to imply that the works of these authors do not merit study), almost no academic criticism of fantasy literature exists.

This finding was at once a source of annoyance and a source of encouragement for me. The annoyance stemmed (and stems) from the implication of a lack of scholarly criticism: unworthiness; I have been reading fantasy literature for many years, and to imply that the activity on which I have spent so much time is worthless is insulting to me. The general dearth of scholarly treatment of the genre means, however, that the field for working with that genre is wide open, hence the sense of encouragement; if others have not or do not treat fantasy literature seriously, then I have a great deal of space in which to so do, and I can be on the “ground floor” of a body of critical work on the genre if such a thing ever comes to be (as it should).

This paper rises from that sense of encouragement, and is an attempt to begin, if only in a small way, to create the body of fantasy criticism that is the natural outgrowth of Tolkien’s assertion (made in “On Fairy-stories” and with which I agree) that fantasy literature has the same intrinsic value as any other mode of literature and should be treated similarly. In it I intend to analyze how Robin Hobb nuances in her Farseer trilogy one of the central tropes of fantasy literature: the warrior-hero. This will require a brief discussion of the nature of the warrior-hero in fantasy literature, and contextualization of Hobb’s work within the genre of fantasy literature.

I. The Importance and Definition of the Warrior-Hero in Fantasy Literature

Fantasy literature cannot function without the warrior-hero. From its earliest incarnations to its most recent manifestations, fantasy literature concerns itself almost exclusively with the interactions of warrior-heroes with the worlds in which they exist, whether those interactions are those of a student coming into adulthood or those of a tried and proven combatant asserting power or those of a past master passing on a lifetime of experience to the next generation.

Oberon by GENZOMAN on DeviantArt, here, used for commentary

The epics, which are the earliest examples of fantasy literature (that being literature which employs a significant element of non-human or non-humane beings or non-technological abilities, usually evidenced in “races” such as elves or in powers commonly called “magic”), center around the dealings of warrior-heroes; the Iliad recounts the conflict between Achilles and Agamemnon, both warriors of renown, at Troy; Beowulf the exploits of its eponymous character whose hand-grip employs the strength of thirty men and whose fame comes chiefly from his displays of combat prowess. Later works that can easily be called fantasy or which certainly have fantastical elements also center around the doings of warrior-heroes; Book 1 of Spenser’s Faerie Queene relies on the fighting of the Redcrosse Knight and Prince (not yet a king, acting not as the “standard” legend states but as a young nobleman of the Middle Ages “ought to” and performing errantry) Arthur, and Le Morte D’Arthur is nothing but a series of actions of warrior-heroes. Moreover, the plot of The Lord of the Rings, that lynchpin of fantasy literature, would not have been able to occur without Aragorn or Éomer, warrior-heroes both.

These fantastical warrior-heroes, and many others like them, exhibit certain common qualities. Principal among these is martial prowess; one cannot be a warrior-hero without being a warrior, and one cannot be a warrior without knowing how to fight and fight well—victory in the fight contributes in no small way to becoming a warrior-hero. Additionally, the warrior-hero is nearly always sworn to something greater than him- or herself; Gilgamesh is obligated to the realm he rules, the heroes of the Greek epics are at Troy to answer a vow, Beowulf is described as the “thane of Hygelac” (Beo. line 192), and though both Aragorn and Éomer become the rulers of their respective nations (which positions are in some respects positions of servitude and require swearing to the realms and to one other’s realms) they both also explicitly serve others, most notably Théoden, during the course of the narrative in addition to showing Gandalf no small amount of deference.

Martial prowess and deference to higher authority are not enough, however, to create the warrior-hero; many competent fighters honorably discharge their sworn duties to their nations and are not warrior-heroes in the sense of the fantasy trope. A fantasy warrior-hero is in a position of command; Gilgamesh is “called a god and man” (15), Agamemnon and Odysseus are both the kings of their respective nation-states, Beowulf is in the royal line and becomes king of the Geats, and knighthood such as held by the Knights of the Round Table is often a position involving governance—many of Arthur’s comrades are lords over their own territories. Further, a warrior-hero does not govern from a place of safety, but hazards him- or herself alongside his or her fellow warriors; Achilles (when he fights) is perpetually at the center of the battle, the Redcrosse Knight and the Knights of the Round Table engage in repeated single combat, and Aragorn and Éomer meet “in the midst of the battle” for the Pelennor Fields after literally having cut their ways there (Tolkien, Lord of the Rings V.6.135). Additionally, the fantasy warrior-hero is from his or her earliest incarnations directly connected to the otherworldly, and typically in a “good” way, by descent or equipment or friendship or a combination of them; Achilles’ descent from Thetis and arms from Hephaistos (Il. 1.276-79, 18.330-616), Odysseus’ enjoyment of the favor of Athena (Od. 1.51-55), Arthur’s Excalibur and his advisor Merlin, and Aragorn’s descent from all the major houses of both Elves and Men—which include a being who existed before the world (Tolkien, Silmarillion 379-382, 390, 423)—all exemplify this.

From these examples, a workable definition of the fantasy warrior-hero can be created; the fantasy warrior-hero is a figure of authority “blessed” by that which exists beyond the normal bounds of reality and who possesses significant martial prowess which is directed toward “greater” ends than him- or herself. The protagonist of Robin Hobb’s Farseer trilogy does in many respects meet this definition, albeit not in the way the examples from which the definition is formed do. This is perhaps related to the fairly nuanced place Hobb herself occupies in the field of fantasy writers.

II. Hobb’s Position in the Genre of Fantasy

In many respects, Hobb’s writing is typical of the fantasy genre; her works occur primarily in a loosely Western feudal society in which a sovereign king holds the allegiance of lesser nobles (all of whom field their own military forces) and in which, though there is a definite division between social strata, even the lowest-born have certain rights and prerogatives upon which even the king cannot tread—“The welfare of the people belongs to the people, and they have the right to object to it if their duke stewards it poorly” (Hobb, Apprentice 1, 65, 83-84, 139, 271; Quest 205, 332, etc; Royal 97, 231, etc). She also, as do a number of other fantasy writers, invokes decidedly non-Western societies, some of which are wholly of her own invention rather than allegories of other cultures in the “real” world (Hobb, Apprentice 70, 344+; Quest 120-134, 198, 381, 530). The primary society in her work, that of the Six Duchies, follows in the tradition established by Tolkien and boasts technology roughly equivalent to that available in Western Europe between the Second and Third Crusades, utilizing axe, sword, bow, mail, and boiled leather in warfare, dwelling in fairly large—and clean—stone castles, and utilizing both oar and sail in their ships (Hobb, Royal; Tolkien, Lord of the Rings V). Hobb also echoes Tolkien in portraying a war where the primary society is beleaguered the consequences of which will reach far beyond the realms directly involved in the fighting, though Hobb diverges from Tolkien’s model in that the Duchies display a far greater equality of genders than does Middle-earth (Hobb, Apprentice 58-62, 83-84; Royal 117-18, 153, 304, 499-506; Quest 389-93, 739; Tolkien, Lord of the Rings V.61-62). Hobb’s writing further treats magic liberally, much more so than does Tolkien’s, noting as is common with fantasy writers high and low forms of that otherworldly power (Royal 1-2; Quest 2-3, etc.).

Hobb, however, utilizes in the Farseer trilogy the technique, unusual to fantasy literature, of a first-person retrospective narrative interspersed with notes almost editorial in their form; fantasy literature typically employs a third-person omniscient narrator, while Hobb’s protagonist provides the details of the action in the text, freely intermixing simple recountings of events with bouts of nostalgia. With this technique, she portrays her protagonist, FitzChivalry Farseer, as an older man, scarred by battles, addicted to the use of magic and a drug that eases the first addiction, removed from the fellowship of most other people, and honored in only the most covert ways for the deeds he narrates, similar to the way in which Tolkien depicts Frodo Baggins at the end of The Lord of the Rings (Hobb, Apprentice 1-3; Quest 754-57; Tolkien, Lord of the Rings VI.341). While Frodo is not strictly a warrior-hero, FitzChivalry Farseer, about whose combat exploits songs are sung—his “deeds sung of as noble and now near legendary” by a minstrel—and who literally dies—“confined to dungeon and then coffin”—in the process of serving the royal line of the Six Duchies, certainly is one, and it is his warrior-heroism that Hobb deftly nuances (Hobb, Royal 332-34, 510; Quest 2-3, 236-37).

III. How Hobb Nuances the Warrior-Hero

As stated above, in fantasy literature the warrior-hero is a figure of authority “blessed” by that which exists beyond the normal bounds of reality and who possesses significant martial prowess which is directed toward “greater” ends than him- or herself. Discussing how FitzChivalry Farseer incorporates each part of that definition will demonstrate how Hobb nuances that fantasy trope.

Throughout the Farseer trilogy, FitzChivalry holds a position of authority, though that authority is never absolute and shifts dramatically based on the situation in which he finds himself. From the opening of the first book, when the first-person narrative begins, he assumes some authority over even the reader; he is the mediator through which the reader experiences the Six Duchies and the events of the Red Ship War. Shortly thereafter, FitzChivalry begins to relate his own experiences rather than presenting his musings on the nature of history, and the reason for his peculiar name is made plain; he is the bastard son (hence the “Fitz,” which is quickly applied to him) of the heir apparent to the throne of the Six Duchies, a man named Chivalry (Hobb, Apprentice 5-11). While bastardy is not the most auspicious origin for a warrior-hero, it does have certain advantages; soon after FitzChivalry is brought to the capital of the Six Duchies, his grandfather, King Shrewd, lines these out to the youngest of his own three sons. Being “a diplomat no foreign ruler will dare to turn away” or the potential foundation of “[marital] alliances” is certainly more in line with the traditional warrior-hero concept than illegitimate origin, though even this is nuanced by the king’s mention of the utility of having a bastard to work “the diplomacy of the knife” (49-51).

The authority FitzChivalry holds is invoked and evoked at several later points in the trilogy. He is at one point sent along with his uncle, Verity, to investigate and correct a deficiency in one major nobleman’s execution of his defense duties; while on this trip, he ostensibly serves as a dog-boy to his uncle, but is bidden to be ready to execute the King’s Justice in the form of assassination should it be needed—both positions of authority, albeit dubious—and in the former guise sharply issues orders to the wife of the major nobleman in question before counseling her to steer her husband to a better course of action (127-62). Later, he represents Verity—who awarded him a heraldic emblem of his own—to his fiancée in a politically-based marriage, a position of honor if of mixed intent, for FitzChivalry is bidden to kill the heir to another realm while on that journey (355-426). Some time later in the trilogy, FitzChivalry is offered lands and a title although he rejects them, and still later serves as a formal witness to a ceremonial request made of the king by a prince of the realm, again a post of honor though an inactive and minor one (Hobb, Royal 323-25, 374-81, 595-96). Partly as a result of the request he witnessed, FitzChivalry is offered a chance at regency of the Six Duchies, which would be an exceedingly elevated position save that the offering skirts the very edge of treason—“not treason, quite, and yet…” (591-98). In each instance of FitzChivalry being offered or exercising power, there is a taint or a twist that shades it.

FitzChivalry’s magic is similarly nuanced; in him are combined the “highest” and “lowest” of mystical disciplines, the royal Farseer Skill—which allows human minds to touch one another and speak and can allow a greater dominance by one over another than does any physical force—and the much feared and hated animal-magic of the Wit—which fosters a sense of the life of the world and a permits a sharing of being, not dominance but union in mind and heart and spirit, between human and animal—respectively (Hobb, Royal 1-3). The former, in which he is trained at the king’s express command and—“the Skill is not taught to bastards”—against all tradition (Hobb, Apprentice 248, 254, 262), allows him to lend mental strength to his prince for the defense and maintenance of the Six Duchies (Hobb, Apprentice 287-88, 332-33, 425-26; Royal 326-27; Quest 697, 699, 711-17). The latter, the Wit, is reviled in the Six Duchies, a foulness considered curable only by hanging, drawing and quartering, and burning its practitioners—“it was never accounted a crime, in the old days, to hunt them down and burn” users of the Wit—though to point up a nuance, all people have a measure of it (Hobb, Apprentice 38-43, 263; Royal 652-55, 674-75; Quest 606, 673-76). FitzChivalry uses both Skill and Wit throughout the Farseer trilogy, sometimes to good ends and sometimes to bad, but they ultimately operate in juxtaposition to their “popular” perceptions; FitzChivalry and his prince are betrayed almost to the point of ruin through the Skill, and FitzChivalry wakens the salvation of the Six Duchies through the Wit—“Blood and the Wit…can wake the dragons” in which Verity places his hopes for the salvation of the Six Duchies (Quest 480, 610-58, 738). The noble becomes a device of treachery and the base saves all; magic becomes nuanced.

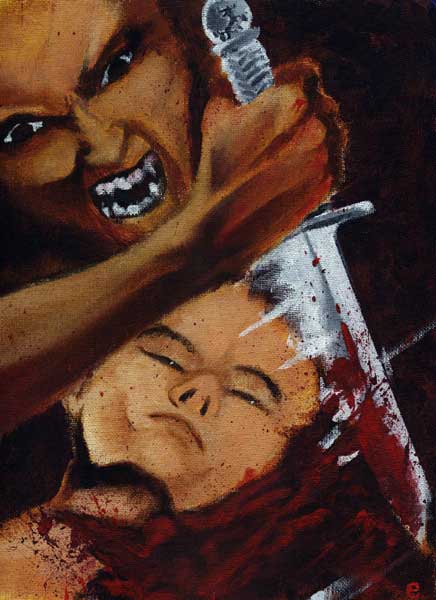

Squeal like a pig by baccanal on DeviantArt, here, used for commentary

More nuanced than the supernatural aspect of the character of FitzChivalry Farseer is his martial prowess. That he excels at killing other human beings is not an open question; he is trained from a very early age to work “the diplomacy of the knife” and excels in his work as an assassin—his teacher notes his “gift for this,” FitzChivalry notes that “over three months [he] killed seventeen times for the King,” and he is able to manipulate circumstances to inflict a shame worse than simple death (Hobb, Apprentice 50, 71-78, 84-89, 323-24; Royal 114-21, 256-67; Quest 174-87). Sneaking about in silence and stealth to slip blades between the ribs of the sleeping or slipping poisons into food and drink and other things are not, however, typically named the activities of warriors; Hobb acknowledges this in the titling the Farseer books “Assassin,” a term with few, if any, pleasant associations. Yet FitzChivalry also acts as a warrior in a more traditional sense of the term. As was mentioned earlier, his warrior exploits are set into song, as befits one who charges headlong into a fight to defend besieged comrades or his queen (Hobb, Royal 144-45, 332-34, 499-509; Quest 236-37). As was also mentioned earlier, he is acknowledged to be of royal blood even through his bastardy; he is, accordingly, trained to make war (Hobb, Apprentice 58-62, 68, 306; Royal 270-73, 312-21). Even so, he does not have the best of luck in direct combat; he suffers considerable injury nearly every time he engages in an open fight—Verity notes that “the most distinctive part of [FitzChivalry’s] fighting style is the incredible way [he has] of surviving it” (Hobb, Apprentice 257-63, 406, 422-23; Royal 265-70, 284-85, 618-20; Quest 374-80, 729-39). FitzChivalry fights, but instead of a warrior’s clarity, he finds confusion and nuance.

Martial prowess, though, can be directed against right, magic against the wise, and authority against those who grant it unless those who have those things hold fast to their devotion to powers greater than themselves. For the most part, FitzChivalry is loyal to the Farseer dynasty; in his youth, he is claimed for the dynasty by his grandfather—though in purchase, which nuances what might have been normal filial piety; in his upbringing, he comes to love and trust his mentor; in his manhood, he comes through love to follow Verity and Verity’s queen (Hobb, Apprentice 50-52, 56, 86, 89-101, 147; Royal 6-7, 15, 53, 60, 84, 124-30, etc.). Yet even this loyalty, this devotion to duty that impels FitzChivalry to drug himself—knowing the risks of so doing—and set out in a berserker rage while Verity’s queen, Kettricken, escapes from danger by a route he plans—an action that ends in his own death—is shaded away from purity (Hobb, Royal 557+). From his childhood, FitzChivalry dislikes and mistrusts the youngest son of King Shrewd, one Regal, to whom he does owe loyalty as a member of the Farseer dynasty—though the dislike and mistrust are justified in part because of Regal’s childhood mistreatment of him and later attempt to have him killed as part of a plan to overthrow Verity, providing further nuance (Hobb, Apprentice 15-18, 47, 405-423). The antagonism between the two continues throughout the trilogy, and is in its repeated manifestations justified, imbedding greater complexity in the relationship between FitzChivalry and his legitimate relatives; Regal orders that FitzChivalry be tortured and later hires a hunter specifically to pursue him, while FitzChivalry in turn attempts to kill Regal and eventually uses his Farseer magic to brainwash Regal into zealous, if short-lived, loyalty to Kettricken and her child—he notes that “[the] fanatical loyalty [he] had imprinted on him would be [his] best memorial…Queen Kettricken and her child would have no more loyal subject” (Hobb, Royal 647-52, 661-66; Quest 49, 185-89, 374-80, 751). The FitzChivalry/Regal antagonism leads also to a complication of other devotions FitzChivalry holds; after his aborted attempt to kill Regal, Verity, the Farseer to which FitzChivalry is most loyal, lays FitzChivalry under a geas that does not let him rest until he comes, after a not inconsiderable and quite dangerous journey, to stand in Verity’s presence (Hobb, Quest 192+). Devotion to a greater power, which should be a thing unmarred and easily defined, becomes nuanced in FitzChivalry as do the other traits of a fantasy warrior-hero.

IV. Conclusion

The fantasy warrior-hero is a figure of authority “blessed” by that which exists beyond the normal bounds of reality and who possesses significant martial prowess which is directed toward “greater” ends than him- or herself. FitzChivalry Farseer is a figure of authority, possesses abilities that transcend “normal” reality, is a capable combatant, and devotes himself to the kingdom of his upbringing. He is also reviled, cursed, repeatedly injured, and provoked to treason and to a sundering of his active service. He is a warrior-hero, and he is also a man much like any other; no happy ending is guaranteed to him, but he ends up doing as well for himself as anyone can truly expect to do, if not far better. Given that his warrior-heroism is as nuanced as Hobb makes it, his leaving it behind at the end of the Farseer trilogy is no tragedy, adding one final nuance to the many shades of steel-gray of his life.

Works Cited

- Beowulf. Eds. C.L. Wrenn and W.F. Bolton. 1953. Exeter, England: Univ. of Exeter Press, 1996.

- Gilgamesh: A Verse Narrative. Trans. Herbert Mason. 1970. New York, NY: Mentor, 1972.

- Hobb, Robin. The Farseer: Assassin’s Apprentice. 1995. New York, NY: Bantam Spectra, 1996.

- —. The Farseer: Assassin’s Quest. 1997. New York, NY: Bantam Spectra, 1998.

- —. The Farseer: Royal Assassin. 1996. New York, NY: Bantam Spectra, 1997.

- Homer. Iliad. Trans. Robert Fitzgerald. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1974.

- Homer. Odyssey. Trans. Robert Fitzgerald. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1961.

- Malory, Thomas. Le Morte D’Arthur. Ed. John Matthews. New York, NY: Barnes & Noble, 2004.

- Spenser, Edmund. The Faerie Queene. Book 1. The Norton Anthology of English Literature. Eds. M.H. Abrams et al. 7th Ed. Vol. 1. New York, NY: W.W. Norton, 2000. 628-771.

- Tolkien, J.R.R. The Lord of the Rings. 1955. New York, NY: Ballantine Books, 1983.

- —. “On Fairy-stories.” The Tolkien Reader. New York, NY: Ballantine Books, 1966.

- —. The Silmarillion. 1977. New York, NY: Ballantine Books, 1982.

[…] Fitz subverts expectations of common fantasy protagonists (about which I write somewhat ineptly here) is in treating such concerns; protagonists typically either need not treat them or never know they […]

LikeLike

[…] I presented this paper at the 2019 International Congress on Medieval Studies at Western Michigan University in Kalamazoo, Michigan (about which, see here and here). After some thought and consideration, and given the other work that I am doing, I figured I’d post it here in the hopes that it would be of some help to others–and a better bit of work than I posted at this time last week. […]

LikeLike

[…] might well be the end of it–but Fitz is not a “normal” fantasy protagonist, as I have argued in more than one place, and so it makes sense that another ending might be in […]

LikeLike

[…] Farseer novels, Hobb positions her protagonist as distinctly other than the typical fantasy hero. I’ve argued the point, so I’ll not rehash it–but I will note that Wintrow seems to be in much the same mold, […]

LikeLike

[…] doing helped me with course papers that became conference papers, a publication that later became a blog post, and my master’s thesis.) I know it annoyed some of my high school and earlier teachers, who […]

LikeLike

[…] Geoffrey B. Elliott, “Shades of Steel-Gray: The Nuanced Warrior-Hero in the Farseer Trilogy,” St… […]

LikeLike

[…] note, though, on this rereading that Fitz himself seems to fit the criteria, if only as loosely as he fits being a hero. Coming out of a quiet, clandestine retirement after years away may not be a return from Avalon, […]

LikeLike

[…] tensions between verisimilitude and the fantastic are persistent in the Elderling corpus, and while I’ve spoken to them previously, there’s doubtlessly more that can be said on the matter–and more than I’m […]

LikeLike

[…] Tolkienian epic fantasy even if there are some adjustments in sourcing from North America and focus on a less-noble character) and the position in the book. Dropping the deuteragonists down a hole may seem something of a deus […]

LikeLike