Read the previous entry in the series here.

Read the next entry in the series soon.

An excerpt from a letter from Chade to Fitz about Shrewd and the costs of necessary secrecy precedes “Smoke.” The chapter opens with Fitz reaching out to the Fool, thinking the latter dead. Fitz steels himself to leave his friend behind in search of his daughter and is surprised when the Fool lashes out, thinking that the Servants have come for him again. Fitz helps the Fool along, assisted by Lant, and receives report of events. Brief conference about how to proceed is taken, and the Fool offers guidance as to where Bee might be held.

Photo by cottonbro studio on Pexels.com

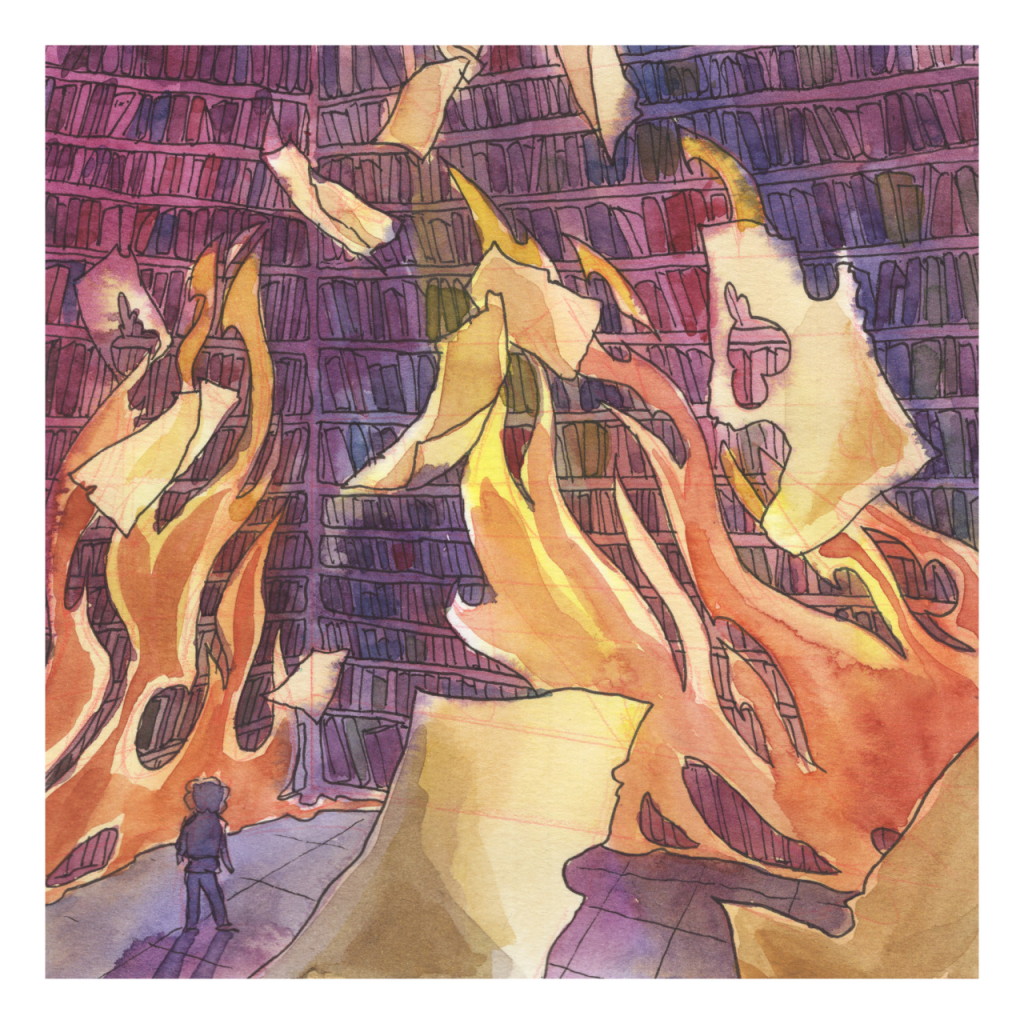

The group finds its way into a torture chamber, Fitz aghast at its contents and implications as he searches among the present prisoners for his daughter. Progress is interrupted by a pair of guards who converse as they make a casual sweep of the area; after they have left, Fitz’s search for Bee continues, uncovering Prilkop. Fitz continues, moving with some caution against the alert status of Clerres, and he becomes aware of fire at work in the stronghold. Fitz and Perseverance charge ahead, the latter passing the former and claiming Bee.

As Fitz makes to begin exfiltration with Bee and his other companions, Wolf-Father rejoins him, making brief report. And in the moment of openness, Fitz begins to be suborned by Vindeliar’s magics, beguiled to take himself and the children to the Servants.

The present chapter offers some explanation for the presence of Wolf-Father with Bee, and I find myself easily able to imagine Nighteyes commenting that “This is pack.” The explanation carries some implications and raises some questions, of course:

- Is Nighteyes unique or rare among wolves in leaving not only an echo of himself in Fitz but a lingering spirit that has agency and can move from person to person? And if he is not, what does that say about the packs of wolves that exist in the world the Realm of the Elderlings inhabits? And what of other animals?

- To what else can such a spirit as Nighteyes is attach?

- What other spirits are at work in the Realm of the Elderlings? (The beings in the Skill that Fitz encounters from time to time, not only those of his Skill-using kin dead or gone into dragons.)

- Are spirit-like manifestations (eg, the apparitions stored in memory stone) merely echoes, or are they, too, potentially lingering sentiences that can “attach” to people and places with agency? (There is some suggestion of this in the interactions between Rapskal and Tellator, for example.)

Such things–and I make no claim that what I note above is exhaustive rather than a few minutes of not-too-deep thinking–are the kinds of things that send fandoms scrambling, I know, and might with some properties open space for other authors (and adaptors; I admit that my recent roleplaying work has me thinking in such ways) to write such that the holes are filled and implications traced out. Whether that is a good thing or not is a matter of perspective; Tolkien’s comments about bones and soup come to mind for one perspective, but my own completion- and lore-seeking self rapidly presents another. (I also acknowledge the existence of but do not care for at least one more: “Who cares?”) I point so much out not because I necessarily do want any of those gaps filled (or, more likely, patched over; I’ve seen how such things can go) but because they are useful reminders that such gaps do not detract from the quality of a work. Rather, they are necessary products of writing that reflects the messiness of reality; while there may be answers to all questions in the readerly world, none of us has all of them, so writing that strives for verisimilitude–such as Hobb’s–should also leave at least things open.

Want writing done at reasonable rates and without AI slop? Reach out through the form below!